Drive Movie Review

After the dialogue heavy films of the 1940s and 1950s, the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and 1970s became just the opposite. Films then were perhaps truest to the idea of 'visual' cinema with not one extra word, not a single needless expression appearing on screen.

Ironically, it was not the art-house cinema that achieved this miracle but commercial movies, and leading the pack were action films. A case can be made of "Bullitt" - an 'action' film where the protagonist barely spoke a few lines.

If you look inside the bonnet of "Drive", you will find the engine that drove "Bullitt" running this film.

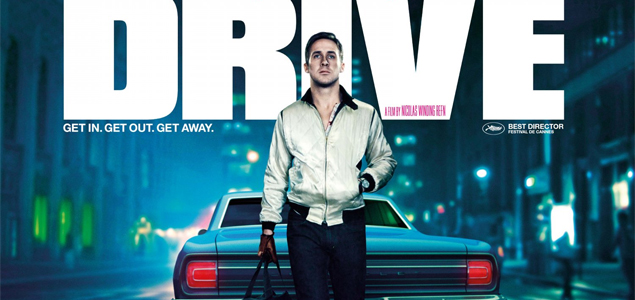

A driver (Ryan Gosling), who's a stunt double in films but moonlights as a driver for criminals, falls in love with his neighbour - whose husband is in prison.

After the husband returns and is forced to pay back protection money or his wife and son would be harmed, the driver gets involved only to find himself a hunted man.

The simple fact that this film relies on visuals rather than words can be found in one tiny detail - the 'driver' is never given a name.

Nor is he really given a back story. It's like he is someone who has appeared from nowhere - a quiet, reticent man who merely observes the violent world around him.

We know him through his actions that evolve with time. He is surrounded by violence and violent men. Even his other profession - that of a stunt double - is violent. Yet, like a lotus he remains calm amid the muck, a smirk permanently fixated behind the toothpick on his lips.

"Drive" is thus seemingly unique and refreshing. But its uniqueness lies in the present context. In the land of a blind Hollywood, the one-eyed is king.

In reality the elements that make "Drive" so endearing have actually been done to death in many spectacular films of the 1970s. Indeed, the character of Ryan Gosling, of a strong, reticent, honourable man is modelled on Steve McQueen's cop character in "Bullitt".

Thus what comes out as a refreshing, art-house take on action, is nothing but an old, 1970s-commercial take on action cinema where a car-chase was not about speed, but about the temperament and poise of the man behind the wheels.

For proof, also watch "Two-Lane Blacktop" and "Vanishing Point". The only difference in the film is a lovely background score that punctuates the silence of the film, and some impressionist slow-motion scenes.

"Drive" is thus a memory refresher of a fascinating time for cinema, where the past of the character was less important than his present, where unrequited love did not fail to inspire men and where the desire of the director was to tell the story as best as possible without worrying whether it's original or cliched.

Today, some might find the above elements disconcerting. Yet "Drive", based on a book by James Sallis, is not a film you'll forget in a hurry. Like good cars, it's meant to last. Just like Hollywood action films of the 1970s.